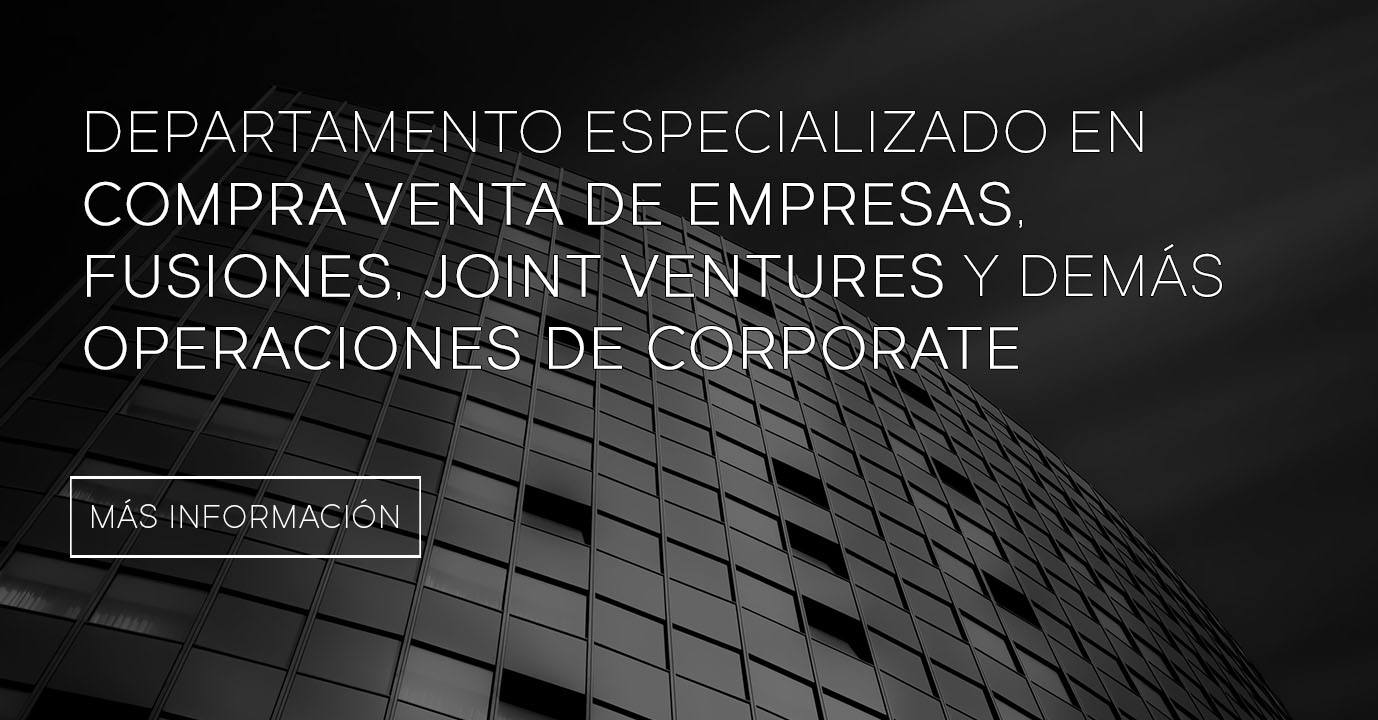

Work contract. Discrepancies between project and execution

In this study we consider the regime of responsibilities derived from the discrepancies between the project of a work and its execution.

In every construction contract it is advisable to include the construction project. This project serves as a commitment for the builder, who must comply with the plan, quality report, measurements, and other specifications contemplated.

In the same way, the project is a guarantee for the builder, since it cannot be held responsible as long as it respects its content.< /p>

It seems clear that the builder must respond to the person commissioning the work (whom we call the principal) when there are construction defects. However, it is worth considering whether any discrepancy between the project and the execution should be considered constructive defect or defect.

We put the following example of a real case solved in our civil law department of this law firm:

The project included the installation of closing panels for an industrial warehouse. The possible liability to be demanded from the builder was raised for having installed panels that were less thick than that provided for in the construction project. The difference was substantial, since the installed thickness was practically half that initially ordered.

The first question that must be asked is whether the change in the thickness of the enclosure constitutes a constructive vice or defect or not. Depending on the qualification that this circumstance deserves, one or another liability regime will come into play.

Considering the definitions of vice [“Poor quality, defect or physical damage to things”] and defect [Lack or lack of the own and natural qualities of a thing. Natural or moral imperfection”] of the Dictionary of the Royal Academy of Language, it is evident that the lesser thickness of the concrete slabs installed when constructing the building cannot really be considered as a vice or defect in this case. Since the smaller thickness of the panels does not constitute any imperfection or poor quality of these materials. The installed panels were intrinsically correct –within their three-dimensional measurements– and were suitable to fulfill the enclosing function attributed. While the vertical delimitation walls of the nave did not constitute load-bearing walls, they should not support the weight of the structure or the roof; the panels only had the mission of separating the interior enclosure from the adjacent properties or exterior surfaces. Then the installation of these elements and not other thicker ones does not constitute any vice or constructive defect.

The fact that there is a discrepancy between the work carried out and the measures cited in the project does not change the conclusion we have just drawn. It may be criticized that the project change was not formally documented to reflect this mutation, but in no way does this imply that what is not such is considered a default or vice. The ship was perfectly valid and suitable to be considered as a ship for industrial use even though thinner concrete plates have been installed. And even more so when in the project the result of the work has not been conditioned to a specific use that required a greater consistency of its enclosing walls.

Since it was not strictly a vice or defect, we consider that the builder was not liable for vices or defects that is regulated in art. . 17.1 LOE.

This precept contemplates a multiple liability regime for damage to the work with different periods of manifestation of the damage: annual, triennial and decennial.

The common denominator is the existence of a defect or vice in the work from which damage or harm to the work is derived. If there is no vice or defect, the consequence is thatthe responsibility of any of the agents involved in the building, including the promoter and the builder, is not enforceable in this way.

The above being true, it becomes clearer that the ten-year liability for vices or defects is not claimable that causes ruin. It does not seem difficult to understand that the nave will not be ruined as a result of its perimeter enclosure having been arranged with less thick panels. If the damage to the construction occurs because someone breaks those walls, the cause of this would not be the least thickness but the abnormal action of whoever hits the walls.

These conclusions do not necessarily mean that the injured party cannot demand responsibility, but of course the claim must be based on different grounds. The most optimal solution will depend on the specific case and requires the analysis of a team of lawyers who are experts in civil law.

In another real case entrusted to this civil law department at J.L.Casajuana Abogados, with a similar controversy, the solution lay in requesting liability from the promoter who sold the newly built industrial warehouse.

Even assuming that we were not dealing with a constructive vice or defect, it was necessary to consider whether the purchaser of the property could claim from the person who sold it, claiming that the thing sold had a different quality or worse benefits than due. Certainly, whoever sells something has to deliver what has been promised (art. 1,461 of the Civil Code) and not something different or worse. Here the responsibility that the seller acquires towards the buyer is based on the purchase contract itself and not on the legal regime established in the LOE. The jurisprudence of the Supreme Court has repeatedly declared that the delivery of a different thing constitutes a breach of contract by the seller when the object sold is totally unfit with the consequent dissatisfaction of the buyer, so that the latter can request the resolution of the sale. with refund of the price and even with the payment of the corresponding compensation according to articles 1,101 and 1,124 of the Civil Code (doctrine aliud pro alio).

For these purposes, it is important to clarify whether the property transferred to the buyer complied with the terms of the contract or not, since this will depend that the obligation to deliver the thing sold is considered correctly fulfilled or not.

The term to bring this action before the Courts is 6 months from the date of sale (art. 1490 of the Civil Code). It is an expiration period and not a prescription, which there is no possibility of interrupting before its exercise (STS July 22, 1971 and judgment of the Provincial Court of Huesca of November 3, 1998 among many others).

Conclusions

First– The installation of elements other than those provided for in the project of a work does not always constitute a vice or constructive defect.

Second.- As it is not a vice or defect, the annual, triennial and decennial liability regime established in the Law on the Management of Building.

Third.- The solution can be found in the general regime of obligations and contracts, or even in the regulations applicable to the sale when the case in question so advised.